I do not think so. I spent a good portion of my career in the so-called DuPont safety culture. Safety, at least when I worked at DuPont, was so interwoven into the overall fabric of the organizational culture, one would be hard pressed to distinguish the two as separate phenomena.

Compartmentalizing safety

Still, organizations encourage workers to compartmentalize safety into toolbox meetings, safety moments, safety investigations, etc. The point is not that safety is unimportant, but that we work in organizations that reinforce the significance of safety through the various rituals. Management wants safety to be integrated into the routine, but we go to great lengths to separate safety into distinct activities and initiatives.

A model to consider

Here is a model to consider employing in your next culture change effort – and you know at some point for some reason there will be a change effort.

A colleague gave me a white paper by Mark Bodnarczuk entitled, “Will Science Survive in the DOE Bureaucracy?”1 I find his approach to change far more robust and uncomplicated then most, and quite applicable to other public organizations and the private sector.2

Bodnarczuk first draws upon the premise from the Human Performance Model that human performance is powerfully shaped by organizational structures, systems and the culture within which employees work. So deep organizational change must begin with the organizational culture, because… people cannot perform better than the organization supporting them.”

Lasting change is rare

Bodnarczuk explains why organizational change is so expensive and rarely results in lasting change. DOE’s dysfunctionality is caused by vertically oriented silos. This is exacerbated by a horizontal stratification between DOE political appointees and long-term federal employees. Management is called the A-team and employees are the B-team, because the B-team will “be” there when the A-team comes and goes. The B-team fights any attempt to change culture that does not build their power base or increase their visibility.3

Bodnarczuk notes the sheer struggle it takes to sustain change.4 Even the slightest hint that employees can return to their previous culture provokes energy to do so. Why? Because employees knew how to navigate through the old culture.

To overcome the obstacles

Bodnarczuk begins with the entire organization taking a hard, introspective look at how it is doing business, where it is headed, and embracing two long-term “fixes.”

1. Practicing safety and health pros must learn to see the nature of their work as including leadership and management competencies needed to run an enterprise.

2. Practicing safety and health pros and administrative staff must learn to see themselves as a cross-functional team.

Fix 1: A New Way of Seeing the Safety and Health Practice

Culture teaches new and permanent members how to see themselves, other people, and the world around them. Safety and health professionals have used their cultural norms to counteract the indoctrinating power of their work culture — talking to fellow colleagues about management not supporting programs and what to do about it.

Today, the scale, cost and complexity of safety and health work forces us to employ a new way of seeing our work. Collaborative approaches build ownership. To own it, employees have to build it and to build it, safety and health pros must learn collaboration skills, project management skills, leadership and facilitation skills. Otherwise, our occupations will slowly die from a thousand cuts.

Fix 2: Safety and Health Professionals and Administrative Staff as a Cross-Functional Team

Operations looks to safety and health professionals to help them figure out how to undertake a task, while safety and health professionals see operation’s requests biased toward avoiding having to follow a safety rule. This leads to a breakdown in trust. This back and forth lack of trust continues to be reinforced, which leads to safety and health pros providing very conservative, no-risk advice. Operations is frustrated and often indifferent toward safety.

Now it’s time to rethink how we all view each other and view safety and health as a cross-functional activity between operations and the other functions of the organization.

Bodnarczuk says something you “see” as a negative can be transformed into something positive by changing how you “see” it.5

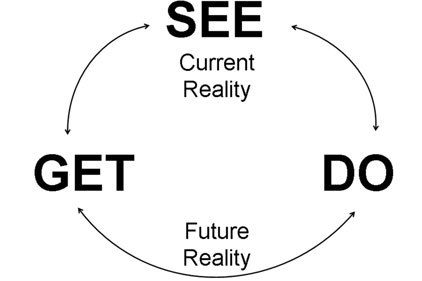

See-Do-Get Process®

The See-Do-Get Process® is simple, but profound.6 First, we see the world and believe it is “reality.”7 When we act (Do), people read our body language and respond to the message they see in us. Their response then reinforces how we see them. We see, we do, we get.

Stephen Covey contends that 55 percent of all communication is visual (body language), 38 percent is voice tone and inflection, and only seven percent is word choice. Ever wonder why email is such a poor form of communication? When a boss or colleague “says” one thing and “does” another, ALWAYS believe what they do, not what they say.8

As time elapses, a pattern of interaction emerges as people cycle through the See-Do-Get process. A couple may go through this cycle many times and not discern the behavioral misinterpretations of each other, yet another person can see it instantly.9

Bodnarczuk concludes, “given the unconscious nature of the See-Do-Get process, is it any wonder that deep change is so difficult to obtain and even harder to sustain?”

Next month, we explore Bodnarczuk’s expansion of the See-Do-Get process to the Island of Excellence® Change Model.

Sources

1 Bodnarczuk, M. 2005. Will Science Survive in the DOE Bureaucracy? Breckenridge Consulting Group Inc. Breckenridge, CO.

2 Ibid. pp. 5.

3 Ibid. pp. 5.

4 Ibid. pp. 6.

5 Ibid. pp. 10.

6 Stephen Covey proposed the see-do-get model to operationalize Thomas Kuhn’s notion of paradigm shifts. Covey, S.R. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. Fireside Book. NY, NY. 1990. and Kuhn, T.S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 3rd ed. U. of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. 1996.

7 Op. cit. pp. 10.

8 Ibid. pp. 11.

9 Ibid. pp. 11.