Why behavioral change is hard

Anyone who’s ever tried to quit smoking or lose weight knows how difficult it is to break old habits or adopt new ones.

Anyone who’s ever tried to quit smoking or lose weight knows how difficult it is to break old habits or adopt new ones.

Most people have to make several tries at it before they succeed. Others get so discouraged, they give up.

But every effort you make in the right direction boosts your chances of success, even if you backslide from time to time, reports the Harvard Women’s Health Watch in its March 2012 issue.

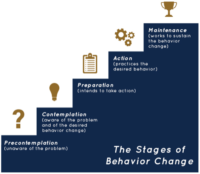

According to one widely used theory (the transtheoretical model of behavior change), change occurs in five stages. Each stage is necessary before you can successfully move to the next, and can’t be hurried or skipped. The entire process can take a long time and may involve cycling back through earlier stages before moving on.

The five stages are:

Precontemplation. At this stage, you have no conscious intention of making a behavior change, but outside influences, such as public information campaigns or a family member’s concern, may spark your interest or awareness.

Contemplation. At this stage, you know that the behavior is a problem and at odds with personal goals (such as being healthy enough to travel), but you’re not committed to taking any action. You may weigh and re-reweigh whether it’s worth it to you to make a change.

Preparation. You make plans to change, such as joining a health club or buying nicotine patches. You anticipate obstacles and plan ways around them. For example, if you’re preparing to cut down on alcohol and you know that parties are a trigger for you, you make a list of alternative activities you can do with friends, like going to the movies.

Action. At this stage, you’ve changed—stopped smoking or lost weight, for example—and are facing the challenges of life without the old behavior. You use the strategies you came up with in the preparation stage.

Maintenance. Once you’ve practiced your new behavior for six months, you’re in the maintenance stage. Here you work to prevent relapses, including avoiding situations or triggers associated with the old habit or behavior.

Successful change comes only in stages. How long it takes is an individual matter.

In fact, no matter when we decide to make a change — or how strongly we're motivated — adopting a new, healthy habit, or breaking an old, bad one, can be terribly difficult. But research suggests that any effort you make is worthwhile, even if you encounter setbacks or find yourself backsliding from time to time.

When it comes to health recommendations, we mostly know the drill: exercise most days, eat a varied and nutritious diet, keep body mass index in the normal range (18.5 to 24.9), get enough sleep (seven to eight hours a night), don't smoke, and limit alcohol to one drink a day. What we do for ourselves in these areas is often more important than what medicine can offer us.

In a 20-year study that followed nearly 6,500 middle-aged and elderly people, those who smoked, were obese or physically inactive, or had diabetes or uncontrolled high blood pressure when the study began were much more likely to require admission to a nursing home later on.

Middle-age smoking increased the chance of a nursing home admission by 56%, physical inactivity by 40%, and uncontrolled high blood pressure by 35%. Diabetes more than tripled the risk. Middle-age obesity was also associated with higher risk, but the association wasn't statistically significant — that is, the numbers could have resulted from chance. All of these conditions can, of course, be modified with lifestyle changes.

Considerable research has sought to identify factors that contribute to successful behavior change and to develop more effective tools for clinicians to encourage their patients to adopt healthier habits, especially in the context of a brief office visit. One potential roadblock: too often we're motivated by negatives such as guilt, fear, or regret.

Experts agree that long-lasting change is most likely when it's self-motivated and rooted in positive thinking. For example, in an analysis of 129 studies of behavior change strategies, a British research group found that the least effective approaches were those that encouraged a sense of fear or regret. Studies have also shown that goals are easier to reach if they're specific ("I'll walk for 30 minutes every day," rather than "I'll get more exercise").

You should also limit the number of goals you're trying to reach; otherwise, you may overtax your attention and willpower. And it's not enough just to have a goal; you need to have practical ways of reaching it. For example, if you are trying to quit smoking, have a plan for quelling the urge to smoke (for example, keep a bottle of water nearby, chew sugarless gum, or practice deep breathing).

Here is a description of the stages of change and some ideas about how people move through them:

Precontemplation. At this stage, you have no conscious intention of making a change, whether it's because you lack awareness or information ("Overweight in my family is genetic; it's just the way we are") or because you've failed in the past and feel demoralized ("I've tried so many times to lose weight; it's hopeless").

People in this stage tend to avoid reading, talking, or thinking about the unhealthy behavior, but their awareness and interest may be sparked by outside influences, such as public information campaigns, stories in the media, illnesses, or concern from a clinician, friend, or family member.

To move past precontemplation, you need to sense that the unhealthy behavior is blocking your access to important personal goals, such as being healthy enough to travel or enjoy children or grandchildren.

Contemplation. In some programs and studies, people who say they're considering a change in the next six months are classified as contemplators. In reality, people often vacillate for much longer than that. At this stage, you're aware that the behavior is a problem, but you still haven't made a commitment to take action. Ambivalence may lead you to weigh and re-weigh the benefits and costs: "If I stop smoking, I’ll lose that hacking cough, but I know I’ll gain weight.”

Health educators have several ways of helping people move on to the next stage. One strategy is to make a list of the pros and cons, then examine the barriers (the cons) and think about how to overcome them. For example, many women find it difficult to get regular exercise because it's inconvenient or they have too little time. If finding a 30-minute block of time to exercise is a barrier, how about two 15-minute sessions? Could someone else cook dinner so you can take a walk after work?

Preparation. At this stage, you know you must change, believe you can, and are making plans to do so soon. You've taken some initial steps — perhaps joined a health club, bought a supply of nicotine patches, or added a calorie-counting book to the kitchen shelf. At this stage, it's important to anticipate obstacles. If you're preparing to cut down on alcohol, for example, be aware of situations that provoke unhealthy drinking, and plan ways around them. If work stress triggers end-of-day drinking, plan to take a walk when you get home.

Action. At this stage you’ve changed – stopped smoking, for example and you’ve begun to face the challenges of life without the old behavior. You'll need to practice the alternatives you identified during the preparation stage. For example, if stress tempts you to eat, you can use healthy coping strategies such as yoga, deep breathing, or exercise. At this stage, it's important to be clear about your motivation; if necessary, write down your reasons for making the change and read them every day. Engage in positive "self-talk" to bolster your resolve.

Maintenance. Once you've practiced the new behavior for six months, you're in the maintenance stage. Now your focus shifts to integrating the change into your life and preventing relapse. That may require other changes, especially avoiding situations or triggers associated with the old habit.

Research has shown that you will rarely progress through the stages of change in a straightforward, linear way. Relapse and recycling are common, though you usually don't go back to square one. The spiral model suggests that relapses provide opportunities to learn what didn't work and make different plans for the next "round."

Relapse is common, perhaps even inevitable. You should regard it as an integral part of the process. Think of it this way: you learn something about yourself each time you relapse. Maybe the strategy you adopted didn't fit into your life or suit your priorities. Next time, you can use what you learned, make adjustments, and be a little ahead of the game.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!