The theory of practical drift postulates that even though organizations develop elaborate plans and procedures for dealing with routine and emergency situations, when a situation (e.g., a fire, explosion, injury, etc.) occurs, these plans and procedures fall prey to on-scene modification due to conditions encountered at the scene.

The drift occurs when responders at the scene do not or cannot follow the pre-established plans and procedures in order to get the job done.

Response plans & reality

From an emergency response perspective, think about emergencies in which you have actually been involved. How often has the response to the emergency unfolded as planned? Rarely, if ever, I would suspect.

Part of the reason is due to on-scene conditions, which constantly change during the event and seldom are the same from one emergency to another. A more embedded reason: the locally evolved practices among responders who use them to get the job done. These local practices are refined over time and are utilized from one emergency scene to the next. With few exceptions, these practices are not documented. They are passed on by word-of-mouth from experienced responders to new recruits.

Now ask yourself, does practical drift occur during routine operational activities?

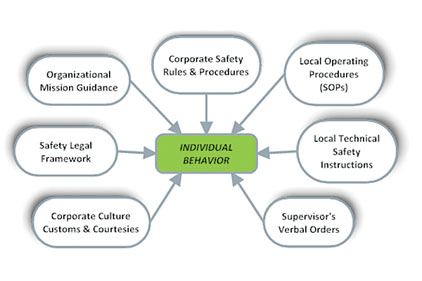

I would posit it does; especially when an operator or mechanic believes the safety procedure they are expected to follow does not make sense, endangers their life, or interferes with productivity. Employees are faced with a plethora of varying pressures, some of which are depicted in the following adaptation of Snook’s “Command and Control Influences on Individual Behavior” depiction2.

Safety professionals and management often take these influencing factors for granted, assuming employees will adhere to the dictates of them as they go about their daily work tasks.

The following factors provide context to how employees think about their work and can influence employee actions:

Organizational mission guidance – Although management spendscountless hours wordsmithing their organization’smission statement, once completemost missions are depicted on fancy postersand displayed in public spaces for all to see.Seldom is an employee asked to provide inputin the creation of a mission statement. At theemployee level, the drift occurs when the missionstatement’s message is not relevant to thework at hand leaving the employee with littleto no ownership in the mission.

Safety legal framework – The overarching legal framework of safety programs originates from federal and state OSHA laws and regulations. Most employers are required to provide safety training to their employees. The drift occurs when the employee returns to his work environment and does not use what he or she has learned, which leads to the employee reverting back to the way work was done before the training. Safety training that is not application oriented, relevant to an employee’s work, and used almost immediately upon return is lost in a matter of days.

Corporate safety rules and procedures – Handed down from the corporate safetyoffice, employees are faced with translating and applyingthese safety rules and procedures into their immediatework environment. Again, rarely are employeesasked to offer their insights on the steps necessary toapply the rules and procedures. Over time, employeesdrift from the mandates of the safety rules and proceduresand institute their own practices to meet theneeds of the job.

Local operating procedures (SOPs) and local technical safety instructions – Local SOPs and technical instructions aretypically followed because often they evolved as aresult of local experiences. The drift occurs as theseemployees deal with varying pressures they encounterdoing their work (e.g., increasing productivity to meeta production deadline) causing them to abandon theirlocal practices for old habits.

Supervisor’s verbal orders – Supervisors carry substantial weight when it comesto giving orders to their employees. Most employeeswill not deviate from whatever the boss asks themto do. The drift occurs when the supervisor expectshis employee to get the job done regardless of therisk. As these supervisor-employee encountersincrease, the employee’s personal appreciationfor risk begins to adapt, which leads theemployee further away from utilizing thenecessary safety measures to ensure an accidentdoes not occur. The supervisor becomesreassured every time one of his crew memberscompletes a task without being injured and thecycle starts all over again. Indeed, the employeeeventually becomes reassured and is willingto take the chance over and over again.

Corporate culture (customs and courtesies) – An organization’sculture, both in the private and public sectors,plays an integral role in the overall performanceof its members and the products theyproduce. The customs and courtesies withinthe culture significantly influence individualbehavior. Individuals adjust their behavioraccording to the ebb and flow of these customsand courtesies, which change with the turnoverof managers and supervisors. The drift occursas an individual’s behavior adapts to the currentstatus of safety with a bias toward revertingto the habits of the past.

Overcoming practical drift

As a safety professional, always consider the influencing factors described above when designing a safety management system or embarking on introducing new safety procedures. Reach out to those who will be tasked with actually implementing the changes you are entertaining and actively involve them in the development of safety practices. Otherwise, those safety changes you want the workforce to embrace will only occur when you are physically watching employees. When you are not watching, practical drift will creep in, and employees will revert to improvising safety practices with which they are most comfortable.

Always remember, safety behavior is all about what employees do when you are NOT looking, not when you are looking.

|

References 1 Snook, S.A. Friendly Fire: The Accidental Shootdown of U.S. Black Hawks over Northern Iraq.PrincetonUniversity Press, Princeton, NJ. 2000. 2 Ibid. pp. 39 |