Rethinking Traditional Safety, Part 5

How we lose safety judgment & skill development

Let’s go back to the last article (March issue) and the importance of the first two critical errors, eyes and mind not on task.

Eyes not on task and mind not on task are involved in a very high percentage of our serious injuries. These two errors had to happen or they have to happen at the same time. Otherwise, if we see it coming, we will almost always get the benefit of our reflexes—which, in most cases, will be enough to prevent a direct hit, blind fall or a head-on collision.

These two critical errors by themselves do not cause serious injuries and fatalities. There are always at least two (or more) contributing factors. But other factors — the type of hazardous energy: electrical, mechanical, thermal; and amount or kind of protection — vary considerably as you go from burn to fall to motor vehicle accident. Still, eyes and mind not on task—happening at the same time—is involved in almost every one. Since mind not on task is bound to happen if you know how to do something well, there is much more “leverage” or efficiency in getting people to put more effort than they are currently making (none) into improving their safety-related habits. Move your eyes first, before you move. Look for line-of-fire potential before moving. Look for things that would cause you to lose your balance, traction or grip, etc.

Favorable Leverage

If eyes on task is so important—and we all know it is—we prove it to ourselves every time we bump into something, bang our shin or stub our toe (See photo). Yet very few adults—unless they are informed, trained and motivated—are making any effort to improve their habit and skills with eyes on task. Just think of the adults you know: do any of them talk about improving their habits with visual focusing? Have they ever asked you for some safety advice? Funny: even though all my friends and extended family know I’m a safety expert, they’ve never asked for any advice… hmm.

Superman complex

Not everybody thinks they’re safe enough already, but most adults do—and for good reason: we all got hurt a lot when we were young. Not all of them needed first aid. Some needed more, like stitches or staples and some needed less.

But most adults will only experience one or two bumps or bruises a week — with only one or maybe two per month that left a mark. Some adults can even go two months without a visible cut, bruise, burn or scrape, but it’s rare. What’s the longest period of time you’ve gone through without a cut, bruise or scrape? Probably not a whole year. Even if it’s as many as two or three a month, the point is it’s not a high number any more.

If you think you’re safe enough already, it makes sense that you wouldn’t necessarily be all that motivated to put some additional effort or any effort into improving your habits and skills with eyes on task. Adults do not—as a rule—put any effort into improving their personal safety skills and habits. We don’t bump into something or somebody every time. So we start to improve rapidly when we are young and as we get better, the frequency of problems gets less, the pain is less frequent and eventually, we all find our own equilibrium. After that, in terms of personal safety skills and habits, most people stop improving. But the concept of equilibrium doesn’t stop with human error or critical errors like eyes not on task.

Equilibrium/safe enough

The concept of equilibrium also spills over into decision-making: if we think we’re going too slow, we put our foot on the gas, and if we think we’re going too fast, we put our foot on the brake. Eventually, everyone who drives faster than us is an idiot and everyone who drives slower is a wiener. After that, just like with the errors, the questioning of the judgment and improvement in judgment stops. This compounds or reinforces the “I’m safe enough” perspective. It makes sense why we’re not getting any better with experience, but that’s not the way most people think. And this is a huge, somewhat painful or at least disappointing mindset.

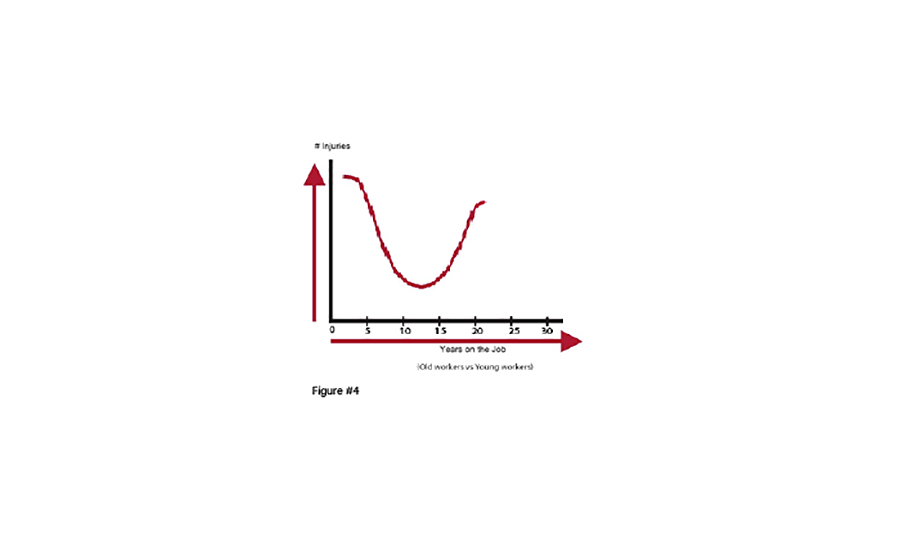

Imagine being at a family dinner. The son-in-law is arguing: “Well, I should know, I’ve been driving for 12 years…” to which his father-in-law says, “Yeah, well I’ve been driving for 36!” As if, for some reason that would make him any better or safer. But the fact is we sensed the risk of driving going down in those first few years as we got more skilled. (See Figure #3)

It’s natural to think the risk would just continue to go down as we gained even more experience, which is why the father-in-law believes his additional 24 years makes him better/safer. In reality, the risk of the two critical errors happening at the same time is actually going up. Why? Most people think our experience is an asset. And overall, it is. But unfortunately, from a neuroscience (reticular activation system) point of view, experience can make keeping your eyes on task and mind on task very, very difficult—especially in familiar surroundings.

As soon as the skill or fear is no longer pre-occupying, your mind can wander. It happens without our permission. Without our permission or any conscious thought—we just started driving on auto-pilot. You can’t stop complacency leading to mind not on task. It’s not a character flaw. There are ways to bring your mind back on task—very efficient ways, but nothing can really stop it from happening in the first place. It’s just the way we’re “hard-wired.”

Unfortunately, the more experienced you are, the more likely it is that your mind will wander. But we can all work on improving our habits with eyes not on task, with fairly little effort and without having to spend any money, so that our automatic behavior or habitual behavior will help to compensate for it—like leaving a safe following distance when driving. Then, even if your mind goes off task and you start driving on auto-pilot, your subconscious will keep that same safe following distance for you.

Conclusion

We all eventually conclude that we’re “safe enough already.” From a neuroscience perspective, this is exactly the time when the risk of making a mind not on task error and an eye not on task error at the same time starts going up. To make it worse, most people think the risk continues to go down as they gain even more experience, when in fact it continues to increase. And unless it is counter-balanced with some additional effort to improve eyes on task, the overall risk of serious injury and/or fatality goes up. (We know) very experienced workers or very experienced drivers are the second highest category or risk group. (Figure #4)

Why young, untrained and inexperienced workers or drivers get hurt is easy for most people to understand. But why experienced workers get seriously hurt and how often they are killed has always been very difficult to explain with conventional risk assessment tools. Hopefully this article sheds some light on the subject. More importantly, you also know what to do about it: improve your safety-related habits with eyes on task. This will be a huge help.

Next issue: The state-to-error risk pattern and the concept of self-triggering.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!