You can’t measure all safety’s intangibles

Managers are typically accountable for outcome numbers. They use outcome numbers to direct the behavior of those who report to them. Most followers or subordinates of managers are assigned their subordinate responsibilities and did not choose their manager. In safety, outcome numbers are based on the relatively rare occurrence of an injury. These numbers (e.g., total recordable injury rate or TRIR) are reactive, reflect failure, and are not diagnostic for prevention.

ROI myopia

Managers focus on numbers. In safety this means injury records and workers’ compensation costs. When I discuss people-based safety principles and procedures with managers, inevitably the question arises, “What’s the ROI or return on investment?” Managers focus on how much a process will cost and how long will it take for the numbers (as in TRIR) to improve. This approach is reflected by the popular management maxim, “You can only manage what you can measure.”

This numbers-based analytical mindset has caused behavior-based safety (BBS) to become much less effective than it could be and should be. All too often, the focus of BBS is on numbers. Managers want to see the number of behavioral observations and completed checklists continue to increase. This ignores the real purpose of BBS — to engage employees in meaningful behavior-based communication about how to work more safely and achieve a vision of “zero harm” (Geller &Veazie, 2014).

A BBS focus on collecting numbers for a computer database and a statistical analysis leads to the repeated use of the same behavioral checklist per work area, and workers “pencil whip” checklist completion. The critical purpose of the observation-and-feedback process — an actively-caring-for-people (AC4P) conversation — is missing. Managers celebrate invalid and inflated “percent-safe scores,” rather than recognize the more important engagement of workers giving on-the-job feedback to prevent injuries.

Safety’s intangibles

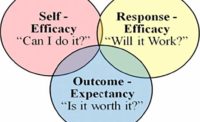

Leaders surely appreciate the need to hold people accountable with numbers. They also understand you can’t measure everything. Some things you do and ask others to do because it’s the right thing to do. Leaders believe it’s important to increase things you can’t put a number on — self-esteem, self-efficacy, personal control, optimism, and a sense of belonging. These five intangibles are person-states that influence people’s tendency to perform or go beyond the call of duty on behalf of another person’s safety, health, or well-being (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Five person-states that influence propensity to perform AC4P behavior

Everyday leadership

Leaders do things on a regular basis to inspire these person-states in employees throughout a work culture. They don’t worry about measuring their own direct impact on these intangibles. They have confidence in the research that indicates promoting these five states is important for increasing one’s propensity to perform AC4P behavior (e.g., Geller, 2001, 2014a, b). Think of how people take vitamin pills daily even though they don’t notice any measurable, direct impact on how they feel.

It’s a good idea to occasionally assess whether certain actions influence people’s subjective feelings or person-states in the desired direction. This can be done informally through personal interviews, unaided by a score card. It is also a given that certain interpersonal and group activities are useful. Genuine one-to-one recognition increases self-esteem and self-efficacy; behavior-based goal-setting builds personal control and optimism; and group celebrations facilitate a sense of belonging or interpersonal relatedness. Leaders perform and support these sorts of activities with patience. They don’t expect to see an immediate change in the numbers of an accountability system.

Leaders don’t need a monitoring scheme to facilitate their attempts to help people feel valuable and part of an important team effort. Leaders are self-directed and self-motivated, and this helps inspire self-motivation in others. Leaders set an AC4P example knowing full well the positive impact it has on cultivating an injury-free work culture.

Intuitive safety

Bottom line: safety management by policy, directive and regulation is necessary at times to motivate people to do the right things for injury prevention. But this alone will not achieve an injury-free workplace. Safety managers need to know – in an intuitive sense — when it is time to step up and become safety leaders. Circumstances dictate that it’s time to build self-accountability rather than holding people accountable.

And here is the most important takeaway: you do not have to occupy a safety management position to be a safety leader. You can, through empathy, actively caring and listening, help people transition from an other-directed to a self-directed motivational state. Few manage, but many must lead.

This article is excerpted from Scott Geller’s forthcoming book, “Applied Psychology: Actively Caring for People.”

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!